"We are bodies of water." This phrase, which struck me a few years ago when encountered in Astrida Neimanis' work Bodies of Water: Posthuman Feminist Phenomenology, not only points to our physical composition — primarily water — but also highlights the fluid nature of our identities. Through a feminist lens, Neimanis explores how bodies of water disrupt traditional boundaries of identity and advocates for a more fluid understanding of embodiment.

Inspired by Neimanis' insights, I spoke with London-based artist-scientist Nina Gonzalez-Park, one of the 17 participants in the upcoming Unveiling Abstractions exhibitions curated by Zoë Goetzmann and Melissa Vipritskaya Topal. Nina describes herself as a swimmer between worlds — a metaphor that deeply resonates with me. Raised in the US, Mexico and Japan, Nina swims across various disciplines, like arts and sciences, as well as ideologies and cultures, finding home in each. From designing and flying kites to sculpting with metal to inviting audiences to participate in her food workshops, Nina's artistic practice embodies the essence of fluidity and points to the profound connection between art and science.

Photography: Aly Thomlinson

Nina, you've described yourself as a ‘swimmer between worlds’. Can you elaborate on what this metaphor means to you?

It comes from an interview I read with Michel Foucault about André Breton. In the interview, Foucault described Breton as a swimmer between two worlds who found an imaginary space between words so that the experience of words becomes knowledge; they’re no longer just tools. I was reading Foucault a lot at the time and doing research around that era because I'm interested in thought – the currency of thought. That's how I got down that rabbit hole. But after reading that interview, the more I thought about it, the more I identified with the idea of being a swimmer between worlds. I love being in the ocean, but it also refers to the disciplines I’m in between – arts and sciences – and the different cultures I grew up around, the languages I speak and the places I lived in. But it never feels awkward, concrete or solid; it's very fluid.

I find that metaphor very evocative, especially in how it captures the fluidity of your experiences and artistic practice. Considering your background in neuroscience, what inspired your transition into art?

I remember it started in primary school. When we first learned about the Renaissance, we learned about the concept of a Renaissance man – the idea that you should know everything instead of limiting yourself to a specific discipline. My family took that to heart; my siblings and I equally prioritised history, arts and science. When I went to university, though, I had to specialise. I went into neuroscience partially because I was considering becoming a doctor or clinical researcher, but I also wanted to work with people. That's what I knew for sure. However, once I was working as a clinical researcher, I realised that creative output wasn’t just a hobby for me. So I started taking short courses [in painting, printmaking, charcoal and others] and spent two years building a portfolio to apply to an MA in Art and Science at UAL.

What are your thoughts on the relationship between these disciplines?

I think they're just two sides of the same coin. Both of them look at how we exist in the world, or existence itself, or questions of why things happen the way they do. Whether it's a human or an entirely abstract experience; it could be quantum entanglement or surrealism. But in the end, it’s an investigation. So the difference is more in how we as a society have siloed them, which started around the 1800s with the formalisation of the sciences as the sciences. That's when they became more separated. And even within the sciences, they took rigour and method to the extreme. So now we have so much siloing and disintegration that you can have a biologist next to a physicist, and they'll have no idea what the other one is talking about. And then, on the other hand, you have the arts where it went to the other extreme – this limitless expression.

Image: Aly Thomlinson

Having lived in Japan, Mexico and the US, did you notice differences in how people perceive and discuss art and science?

Definitely. In Japan, if we're talking about stereotypes or generalisations, there's a sort of rigour in everyday life, even within the arts. That means that artists in Japan emphasise technicality or technical skill. So that's the foundation of creating art; it takes a much more scientific route. Whereas if you look at the US or here – London – that doesn't exist, even if some schools and institutions encourage or specialise in it. But regardless of culture, people prioritise the sciences because of their utility. It's the fact that because of science, we have refrigeration, we have plumbing, we have electricity, we have phones, we have computers. Just because of how they influence our lives. Whereas with art – because even the fundamental question of what's art is such a difficult question to answer, which I think is part of its beauty – people can't understand it or fathom it.

Is it because it lacks functionality?

It's because there are no limitations within art as an industry or a discipline; the functionality is hard to define, but that doesn't mean it's not there.

That leads me to my next question about your piece Kite (2023), a self-designed and handmade PVC fabric kitesurfing kite you first flew before exhibiting it indoors. Can you tell me more about it?

I wanted to make an installation that I knew I wouldn't get a chance to do in the next couple of years of my career. But then I also wanted to make a highly conceptual work founded in technical skill and design. At the same time, I wanted those two things to exist in the same space and blur the lines between basically all of these worlds I could find. There's so much value placed on functionality, so you have to go the extra mile to understand uselessness for the sake of it, especially when you start integrating disciplines - from being inspired by a wormhole to the engineering and the actual mathematical modelling of the kite. And then there’s the utility of creating and using a flying thing. But then you put it in an art space and call it art.

Kite. 2023. Self-designed and handmade PVC fabric kitesurfing kite, PVC and metal wormhole, 17min film. Courtesy of Nina Gonzalez-Park. Photograph: Younkuk Choe

Did anyone question whether it was art or not?

People were confused. And that was the interesting part; different people's reactions to it demonstrated their backgrounds. Some people were wondering, like, What is that thing there? Others would perceive it as an art object. Then, a kite surfer came along and recognised the kite for what it was. But all of them had such diverse perceptions of it. For the kite surfers who flew the kite with me, it was so hard to wrap their heads around it. Why would one make a kite? And especially one that would be so hard to fly? It was by the end of the day, after flying it, one of them was like, It's like we're trying to fly a Van Gogh [laughs].

And what was the experience of flying it for you?

It was crazy [laughs]. I was getting more stressed as I got closer to finishing the kite because I realised, okay, the plastic fabric I was using might not be durable enough for a high wind speed. But I needed a certain wind speed and direction to get it in the air. Making the kite work was part of the entire piece; it wasn't just the process. I don’t think there's a segregation between concept and conceptual integrity with technical skill and design. Functionality is not separate from uselessness, you know, so if the kite didn't work, that would almost be, I guess, a metaphor for the uselessness of art.

Another side of your practice is sculpture. Last year, your work La Divina Envuelta en Huevo (Primadonna), a welded steel pipe, was a finalist for the Ingram Prize. What draws you to the medium?

Part of it is tactility; not just the tactility and making it but that people can hold sculptures or move around them. I find it comfortable to work with sculpture – with metal – because it's such a rigid and unbending material or medium. At the same time, I think metal is fluid; it's just that you need to know how to use it and how you can create that perception of fluidity or the sensation of fluidity with metals. With La Divina, her structure is all around this organic form, this voluptuousness and circularness. But then I have another sculpture work called taki/tako, which will be in the Unveiling Abstractions exhibition [opening this week]. That one's distorting the spaces we inhabit as an installation to create this perception of fluidity.

La Divina Envuelta en Huevo (Primadonna). 2022. Welded steel pipe. Image courtesy of artist.

Can we also talk about your food workshops? You’ve mentioned that food allows us to share what home means to us, which is why cooking is an art form in itself – and then it’s also science. How do these workshops fit within your artistic practice?

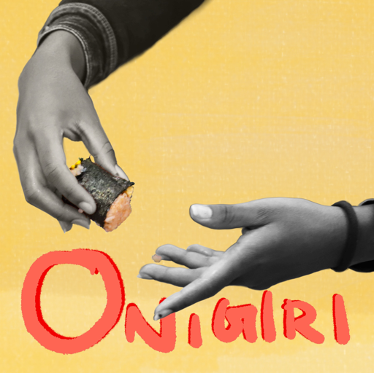

The first workshop was with a Latin American immigrant family. I thought about how I could bring them in to consider that just like everything around us is science, it's also art. Because the reason I started food workshops was to communicate. I was never interested in doing a painting or sculpting workshop because those [practices] are internal to me, while food is how I've always communicated and understood people. It's so inherent in our lives because it's a necessity but also a joy; it's a different way of engaging with art without it being art. And it's fun; I prioritise it being fun. Play is part of the workshop, so the food is always simple – it’s rice balls. So you can't go wrong with it. It can be however you want it to be. It'll taste good. And you can do it with the people you love and care about.

Onigiri. 2023. Workshop and Digital Collage. Courtesy of artist.

With such diverse interests and mediums in your practice, how do you decide what to work on?

I'm glad I worked in clinical research [laughs]. There's such diversity in my practice that it's hard to keep track. I feel like no matter how convergent I try to be, I continue to be divergent. Becoming creative has made me more self-critical about why I am the way I am. Why do I experience some things the way that I do? Why am I making so many different things with so many different materials? And why can't I make one and stick to one thing? And I appreciate it. I love being in an industry and profession that allows me to have that space and investigate that. But going back to your question, I'm grateful to have done clinical research because it's made me very good at planning and time management [laughs]. That's literally it. It's the most boring response ever.

Reflecting on your body of work, what’s the purpose of art in your opinion?

I don't think art has a purpose, necessarily. It's the same as being like, What's the meaning of life? and I don't believe there's a meaning. Like art, just existing is the special thing about it. Science has a purpose, but it also actually just exists. Art is the same in that it can have a purpose; it can be, let's say, very explicitly political because you're trying to move an entire collective consciousness towards a goal. But it can also just exist as a counterbalance to the world we experience. And it's very inherently human.

Cover photography: Sophie Bryer

Nastia Svarevska is a London-based curator, editor and writer from Latvia. She holds an MA in Curating Art and Public Programmes from Whitechapel Gallery and London South Bank University and writes for an artist-run magazine, Doris Press. Her poetry has been featured in Ink Sweat & Tears, the Crank and MONO Fiction. You can find her on Instagram @ana11sva and her website anasva.com.