'A SUDDEN GILMPSE TO DEEPER THINGS': MARK COUSINS ON WILHELMINA BARNS-GRAHAM

- Agnès Houghton-Boyle

- Oct 2, 2024

- 12 min read

Something that Mark Cousins shares with the late modernist painter Wilhelmina Barns-Graham – the subject of his latest documentary – is an inexhaustible creative drive. The Northern Irish director and writer has released a film this year, one last year, and a remarkable six across 2021 and 2022 combined. In total, he has made 24 feature-length films. Mark is deeply interested in cinematic history, the fringes of cinema, and in using film to unearth overlooked and untold stories. His monumental documentary Women Make Film, which premiered at the Venice and Toronto Film Festivals in 2018, is a portrait of the craft told through some of the greatest directors of all time – all of them women. His work has earned a Peabody, the Prix Italia, and the Stanley Kubrick Award and his films have screened all over the world including MOMA in New York and Cannes Film Festival.

I speak with Mark over Zoom one morning from his Edinburgh studio, which is filled wall to wall with materials from his prolific body of work. His latest film, A Sudden Glimpse to Deeper Things, is a thoughtful pouring over the life and mind of one of Britain’s foremost abstract artists, Barns-Graham. Working through the diaries, notebooks and photographs contained within the newly opened archives of the Barns-Graham Trust in Edinburgh – featuring contributions from Tilda Swinton and art historian Lynne Green – Mark examines how Barns-Graham’s deep interest in nature, science, biology and mathematics informed her art and worldview. It is a powerful entry point into understanding the work of an artist who is finally starting to receive the recognition she deserves.

Agnès: One of the key things that really stood out to me having watched your film is the complex ecosystem of the art universe. Art workers of all descriptions – critics, curators, collectors, university lecturers, archivists and others – contribute to bringing an artist to prominence or pushing them to the periphery of history. Your film draws on interviews with some of these people, to tell the story of Willie [Barns-Graham], people who have been supporters of her work. How did you first come across Willie?

Mark: I first came across Willie in 1989 when I was in my early 20s. There was a big exhibition here in Edinburgh and I saw it. I was immediately dazzled by her work which is full of grids and structures. My brain is naturally mathematically inclined, and it was like glimpsing somebody else with that way of thinking across a crowded room. I would try to see her anytime there was a show - often, she'd be put in the context of female or nature painters. Her work on the Glacier, in particular, reminded me of Paul Cezane's fascination with Mont Sainte-Victoire, and his repeated grid-like interest in the famous mountain.

Years later, after reading Lynne’s book, I shared a photo on social media of myself holding up the book, saying: “here I am, outside the house where Wilhelmina Barns-Graham lived.” The Trust, managing her estate, saw the post and invited me to her archive. It’s a bunker, a sort of globe-like cage where all her secrets are kept – and I was just entranced. That's the power of social media, isn't it? They would never have known of my fascination with her, and I would never have encountered them.

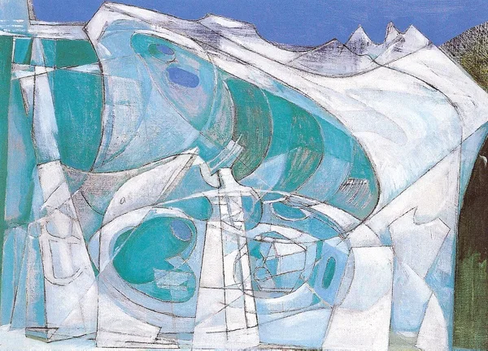

From left to right: Wilhemena Barns-Graham, Glacier (Blue Cave), 1950, Glacier Chasm, 1951

I’m thinking as well about how we consume so much of the art world digitally now. It’s not just the art itself but the way we engage with exhibition guides, press releases, and catalogues. There are countless online art magazines, social media accounts and blogs. Social media and marketing are still considered somewhat dirty words within certain art world contexts but, they are crucial tools for growing an audience and connecting them with artists’ work.

There are certainly terrible downsides when it comes to social media, especially when it comes to the people who run the platforms. But for me, sitting here in Edinburgh, Scotland – which is not New York, it’s not Los Angeles, it’s not Paris – these connections have been incredible. The city’s brilliant, but it’s not these places. Yet through social media, I’m in contact with some of the world’s greatest filmmakers and, increasingly, with people in the art and architectural worlds. Those affinities are invaluable. Connection itself is the heart to creativity. Willie had synaesthesia – which is exactly this – it’s those extra connections in the brain. Overall, I see social media as a very positive thing.

Courtesy of the Wilhemena Barns-Graham Trust

How did the idea of the film come about?

Mark: When I went down to the Trust, I was so excited to see her work. I had no idea she was so productive, right up until the end of her life, creating such a massive body of work. Of course, I’m a filmmaker, and by that point, I’d made 22 feature-length films. It became clear to me, Rob, and Cassia, who work at the Trust, that there was a possibility of making something about her—not a conventional TV documentary or a straightforward biographical film, but a piece of cinema—something with an elegiac quality, a sense of scale, and a focus on sound and atmosphere. I don’t remember who first suggested it, but we all thought, let’s try to make this happen. One of my previous films had been about the drawings and paintings of Orson Welles. The Trust looked at that and, I think, liked it quite a lot. I studied art history and have always been interested in painting, so it seemed like a no-brainer. I had to do it.

In the film you investigate how her brain worked, her synaesthesia and her interest in natural forms and grids to represent the natural world. You then connect her works to the specific contexts of her life, highlighting their formal and mathematical properties. Your film mainstreams her as an artist by providing a framework for approaching her body and understanding her.

There are art historians better equipped to talk about her in an art history context, but I wanted to create a film that uses the language of cinema. I've seen it a few times now, on very large screens, like in 1,200-seat cinemas, and it holds up on the big screen. Her paintings are often quite small but shot with an 8k camera, allows them to be blown up almost to the size of a glacier on the screen.

Art history taught me how to look around an image, to take your eye around it and through it. Virginia Woolf says ‘the eye is not a miner, not a diver, not a seeker after buried treasure. It floats us smoothly down a stream; resting, pausing, the brain sleeps perhaps as it looks.’ I think that art history teaches you how to move around the surface of an image. I think it's been valuable for me as a filmmaker.

Installation shot courtesy of Fruitmarket

While you were working on the film, you also created an immersive multi-screen installation at the Fruitmarket Gallery in Edinburgh. The piece imagines older Willie speaking to her younger self about her climb up the Grindelwald Glacier. Why did you decide to do this?

I had already started working on the film at that time. We'd done our initial filming, and I was juggling A Sudden Glimpse to Deeper Things with other movie projects, but I just felt that I wanted to step away from the idea of a biographical picture. I'm very interested in ageing, my own ageing. My last few films have been about that in some ways. I began to imagine what it would be like to get to a really old age and look back to an epiphany from your youth. What does that feel like? How much do you even remember?

In one part of the film, I have her say to her younger self, “You're happier than I am, but I am a better artist than you. I've seen more.” This sense of accumulating an inner eye. The more glaciers you see, the more sunsets you see, the more art, the more architecture, the more landscapes, all accrue on top of each other.

I wanted to step away from the linear film and do this fifteen-minute piece, which was just about looking back. It's going to Shanghai next, to a huge former warehouse that's turned into a big modern art gallery.

The film begins and ends with reflections on ageing. At the start, you present a series of photographs of Willie as an elderly person dressed in a classic green Macintosh. You ask the viewer what they see and what they might be missing. Then, you close with the installation, which delves into a more introspective look at how she viewed herself in later years. It moves through, how she was perceived by others – both outside the art world and within – to a more introspective look at how she might have viewed herself as an experienced artist.

I wanted to start with a very simple holiday snap of an old lady—the sort of person who is invisible to trendy culture. We all know that as people age, they become less visible, particularly women, and especially if a woman was valued for her beauty, which Willie certainly was. I wanted to start with that sense of invisibility. She didn’t try to dress like a chic Chanel-wearing woman of the '80s on a boulevard in Paris or anything like that.

By starting this way – on the outside, with prejudice – and recognising that that's what happens to women, particularly older women, I could then reveal that within the seemingly mundane image there is something extraordinary: what I call a fire in a box factory, which is the name of one of her pictures. Once you get inside her brain, you realise, my god, this is an astounding human being – exciting, daring, troubled.

This way, the audience feels a bit guilty for thinking ‘That looks like my granny.’ At that age, in her green coat, she was in Barcelona, doing some of her best work, making her most free work.

There is such electricity in her later work, rich luscious colours and sharp piercing lines. It makes me think of the more recent formally abstract films of Betsy Bromberg – her explorations with light and sound.

Mark: And of course, Margaret Tait, here in Scotland.

There’s going to be a special programme of her work at the Barbican next week. Tait is another artist whose work was relatively unknown during her lifetime, and this will be a rare opportunity to see her films screened.

A lot of us have been advocating, guerilla-style, for a revaluation of her work for several decades now. I was one of the people who stuck up plaques to Tait around Edinburgh because, for a long time, her art was seen as domestic, intimate - therefore female and therefore less important.

Willie is often talked about within the context of the St Ives, for obvious reasons, but as we know, you know, Barbara Hepworth got most of the attention of the group. Barbara, shall we say, was not the most supportive person of other female artists. But I'm interested in Willie in the context of international art, and the influence of Sophie Taeuber-Arp or Paul Klee for example. I think we can now start to internationalise her more.

Wilhemena Barns-Graham, White, Black and Yellow (Composition February, 1957

To work so diligently while feeling ignored, to understand that what you are doing has value, and to take yourself seriously requires such tenacity, it takes a very particular kind of person. One of the things Lynne Green says is that knowing Willie totally changed her ambition for what she could do in the world. It’s so impactful. We see this in the film, in the way that she worked and worked things out – the shapes and forms of living things – constantly.

That's why her notebooks are so valuable. They hadn't been seen before, and a lot of her stuff was in boxes. Tilly, the main researcher at the archive, is still, I believe, opening boxes, reading letters and going through diaries. The literal unboxing of Wilhelmina Barns-Graham is continuing into the future.

It’s important that we mention Rowan – her partner, curator, and manager. Rowan stopped doing her own painting to really become the custodian of Willie’s imagination. She was crucial to Willie’s work and did something truly magnificent.

I'm thinking also of Martin Kemp, the art historian at Oxford. He is a huge supporter of Willie and owns quite a few of her pieces. She had people who could see her brilliance, and I have a lot of respect for Martin Kemp for championing her work.

It's a big question, where does confidence come from? I've got creative confidence in my work as a filmmaker, but not personal confidence. It's quite possible to be split. I know a lot of creative people who are like that. Fashions came and went throughout Willie's long career, and art movements came and went. She changed her style many, many times, but she kept working, and she was never trying to follow fashion, which is hugely admirable.

Do you feel you’ve learnt anything from Willie?

I've never really had an off button. I’ve always been a bit manic about work. This is my 24th feature-length film, I’ve made 40 hours of TV, and I’ve just published my sixth book. That’s quite a lot, and I’ve sometimes been suspicious of that drive. But then you come across someone like Willie, who could match me energy for energy, and you realise there’s something deeper at play. It’s what Rilke talks about—the compulsion to create. It’s almost an addiction. In the film, I refer to it as being infected by something. Willie was infected by the Glacier, and now I feel like I’ve been infected by her. She’s inside me now, and she’ll never leave.

Your previous films include Women Who Make Film – a fourteen hour road movie through cinema, that brings to light the crucial yet overlooked contributions of female filmmakers across the years – and Cinema Has Been My True Love, a portrait of Lynda Myles, the first female director of the Edinburgh Film Festival. What draws you to telling these kinds of stories?

On the simplest level, I’m a passionate feminist, so that helps. But beyond that, I’ve been very determined to highlight women's contributions in cinema. With Women Make Film, for example, many of the female directors featured had their work restored, digitised, and subtitled as a result of that project. But, at no point did I talk about the female gaze. The biggest respect I can offer a female filmmaker is to focus on her imagination, her filmmaking—not just her gender.

Many of the living filmmakers involved in that project told me they felt seen because I placed them in the broader context of cinema, not in a subsection. Willie shared a similar sentiment—she didn’t like being labelled a female painter as opposed to just a painter. I’m passionately against gender stereotyping of any sort, including phrases like male gaze and female gaze. I think they’re becoming less useful, and they’re often heterosexist. These bold imaginations—like Willie’s—are leaping the fence and engaging with something much broader, like space, spirituality, structure, and light. Those are the things that are truly exciting.

In the film you talk about having a similar way of thinking to Willie. How did you get into art and visual culture?

I came from a working-class background. There were zero books, we were never taken to museums or theatres or anything cultural. I think that was good for me. I remember discovering a book of Paul Cezanne’s Watercolours in the school library, and it was like, Oh my god, like puberty or something – the intensity of the reaction. I pretty much discovered visual culture for myself. It was just like living my little private, slightly illicit world, through the pictures of MC Escher, of Tintoretto, and the cinema of Orson Welles. Credit to my parents, I was just given the space to get on with the business of art, which none of my family were into – and that helped.

When I said I wanted to be a filmmaker though, there was a deadly silence. My dad was a motor mechanic, and I think that would have gone down a lot better. But because nobody in my family had been to university when I decided that, instead of studying chemistry, I would do art history and film history, nobody said that was weird, because nobody knew what university was about. So again, it was paradoxically liberating. I just acted with a kind of compulsive quality. I felt I needed to be near films and visuals and pictures. I just needed to be near. I didn't know any kind of career path that would have emerged, and I’m surprised it has.

Once I read Rilke’s Letters to a Young Poet, I was like oh - I get you. I read Virginia Woolf's extraordinary diaries and Susan Sontag and thought, people are talking about this compulsion.

A propulsion, of course, but also there’s something really there. You talk about working in various odd jobs after graduating, including as a security guard, before submitting a pitch to channel 4 on a napkin, which was picked up!

It's what I was saying earlier about the difference between confidence in yourself as a person and creative confidence. Gertrude Stein, one of my favourite writers, talks about the sense that you can fully see the work – it just hasn't been made yet. I think Willie could fully see those pictures; she just hadn't painted them. When I start a new film, like the one on Willie, I always start with a sketch and stick to it. I probably did that in less than half an hour. whatever that is, it's very useful to have as a filmmaker.

Agnès Houghton-Boyle is a critic and programmer based in London. Her writing features in Talking Shorts Magazine and Fetch London.