Image credit: Warner Bros Studios

The Art of the Grimoire by renowned scholar Owen Davies is as fascinating as it sounds. Tracing the global history of magic books, from ancient papyri to pulp paperbacks and beyond, the two hundred illustration-rich tome features demonic cartoons, pagan iconography, alchemical engravings and moralistic tableaux. For those who attended the book launch at Treadwell's magical bookstore last Friday, it’s a reminder that palmistry, tarot readings and voodoo dolls have a steeped anthropological and artistic history.

"Wanting to believe that there are higher powers is a fundamental aspect of humankind," says Davies. His book investigates how people have consulted mystics and witch doctors for guidance and remedies since ancient times. Practitioners would record their advice and beliefs onto terracotta plates in the Middle East, bamboo in Asia, and precious stones in Egypt. But it wasn't until parchment became widely accessible in the second century BCE, that they bound their knowledge in rudimentary grimoires.

According to The New York Times, modern witchcraft has grown into a lucrative $2.3 billion industry and boasts a thriving online community of TikTok and Etsy witches who use reels and posts to spread their supernatural wisdom. "Today, people are borrowing cross-cultural ideas in a quest for spiritualism and meaning," says Davies. "This is something we've seen play out in grimoires for centuries."

Divining Witchcraft, Religion and Science

Grimoires are typically endowed with detailed instructions and illustration. "Becoming iconic symbols that transcend their internal content," according to Davies, artists have used grimoire iconography to imbue their works with tension and mystery, or warn viewers about spiritual corruption.

For example, The Witches’ Initiation (1647-49) by David Teniers the Younger depicts a witch teaching her pupil the dark arts from a grimoire. The book is painted as a titular symbol of moral turpitude and power; conjuring devilish creatures that frolic across the canvas. Demonic illustration was rife in Europe during the mediaeval period and the allegorical tale of the magician Faustus (who sold his soul to Mephistopheles for infinite power) saw demonic illustration surge throughout Europe.

"The demon’s character is prolific in magical ideologies across the world" says Davies. "These depictions date back to early antiquity, when ancient civilizations devised rituals to dispel demons from their homes." Demons also infiltrated Arabic grimoires as part-human part-beast jinns, while the Japanese yōkai were malevolent entities capable of shape shifting. The "demonologist" and ukiyo-e artist Toriyama Sekien, accented the Edo period with intricate woodblock prints inspired by yōkai folklore and his own imagination.

For many witches, paganism and religion are like day and night (with the latter historically persecuting the former). But the pair have been inexorably intertwined as numerous cultures adapted various ideologies to suit their own principles and lifestyles. "Religion, science and magic have always inspired one another and constantly overlap in scripture and artistic expression," says Davies.

During the Age of Enlightenment, this overlapping was most prevalent in alchemy (the study of natural magic and transmutation), as academics, alchemical theorists and magicians sought to demystify the compounds of human flesh and spirit. Their teachings were popularised by the European print revolution and a desire to disseminate scientific practice and the arts. Illustrious grimoires exhibited gold leaf and copper-plate woodcut engravings of astrological musings, geometric diagrams and mythological or biblical characters.

Image credit: Yale University Press London

Supernatural surrealism

While women's affinity with witchcraft is undisputed today, magical authorship and artistry has traditionally been male dominated. "Throughout modernity, patriarchal societies have kept the literacy rates for women down, and there were only a few who read or possessed these books," says Davies.

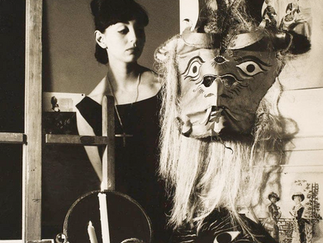

Women's centrality in magical storytelling was to gradually championed post-WW1 to the mid-20th century, as surrealist practitioners like Remedios Varo, Leonora Carrington and Kati Horna (fondly known as the "three witches'') spawned a legacy of metaphysical artworks and Freudian dreamscapes. They're honoured today by contemporary surrealists like Ariane Heloise Hughes and Nooka Shepherd. Infusing their works with feminine energy, both artists are featured at LAMB Gallery's Surrealism and Witchcraft exhibition running from November 16th to December 20th 2023.

Kati Horna, Mujer Con Máscara, 1961

Leonora Carrington, And Then We Saw the Daughter of the Minotaur, 1953

Remedios Varo, La llamada (The Call), 1961

The pair are accompanied by nine other artists including Natalia Gonzalez Martin, Georg Wilson, Bea Bonafini and Leonora Carrington herself. “I find Carrington's work interestingly unique,” says Davies, who was careful to include her work in Art of the Grimoire. “She was obviously inspired by alchemical illustrations from the 16th and 17th centuries and has built a fantastical esotericism into her art- which is not always easy to decode.”

Grimoire Art in Pop Culture

Women's rising role in magical art and industry was also partly down to the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn (a secret magic society of middle-class men and women originating in late 19th century Britain). Although it was fundamentally masonic, the order did publish female members like Pamela Coleman Smith, who illustrated Rider-Waite Tarot deck (the most widely used tarot cards today).

The order's dedication to renaissance forms of mystical alchemy, kabbalah, tarot and geomancy also inspired the forefather of Wiccan practice Gerald Gardner. Come the youthquake of the 1960s and '70s, his ideas enflamed the popular imagination of counterculture movements. “There was a creative melting pot of liberal thinking, expression and socialising," says Davies. "And wicca's mysticism and rejection of traditional hierarchy attracted numerous subcultures."

Grooving to psychedelic and rock music, Hippies and Punks crafted a wicca-inspired lexicon of satanic pentagrams, pagan jewellery and mucha-esque psychedelic concert posters. "There was also a revived interest in H.P. Lovecraft's fantasy horror novels and pulp stories of the 1930s" says Davies; pointing to an entire genre of monstrously mythical “Lovecraftian" art that maintains a cult following to this day.

It seems that the survival of grimoires and magical iconography lies in its ability to capture imagination. Its' ability to ingest numerous cultures and beliefs allows it to evolve in tandem with social trends and ideals. "By representing freedom of expression," says Davies. "Nowadays, magical imagery is associated with unbridled thinking in mainstream media and grimoires are, rightfully, appreciated as tools of empowerment."

Raegan Rubin is a contributing writer for Fetch London.