THEN AND NOW: NOTES ON CIARÁN CASSIDY'S 'HOUSEWIFE OF THE YEAR'

- Agnès Houghton-Boyle

- Nov 19, 2024

- 4 min read

Ciarán Cassidy’s Housewife of the Year, which premiered at CPH:DOX, won Best Irish Feature Documentary at the Galway Film Fleadh and Best Documentary at the Newport Beach Film Festival in LA. Last week, it screened at the Irish Film Festival in London. The documentary traces the profound transformation in women’s opportunities and experiences over a generation through interviews with contestants from the hugely popular television show, which aired on Ireland's national broadcaster, RTÉ, from the mid-sixties until its cancellation in 1995.

Trailer courtesy of WildCard Distribution via YouTube

The messaging and format of the Housewife of the Year competition would have already felt dated to other Western countries by the time it aired. Feminist movements were gaining ground in the UK and across Europe; women were beginning to demand greater autonomy around the world. Yet the social freedoms that other nations began to introduce during the mid-sixties – with liberalised access to the contraceptive pill, divorce and an expansion of employment opportunities for women – remained unconstitutional in Ireland and the Housewife of the Year competition reflected these values.

I’m thinking about the show in relation to popular contemporary lifestyle influencers – often middle and upper-class women – who promote an idealised version of domestic life. It is mostly cookery videos of women preparing meals for their families – unlike the generation of celebrity cooks like Nigella Lawson and Martha Stewart, whose presence in the kitchen carved out a space in a culinary world that had been dominated by men – the tradwife content creator emphasises a traditional role within the home. It is an ideal version of womanhood, which looks peaceful, manageable and, above all, safe. That this content (although divisive) appeals to audiences, can be seen as a reaction to the pressures of modern burnout culture and, principally, the financial instability of our times.

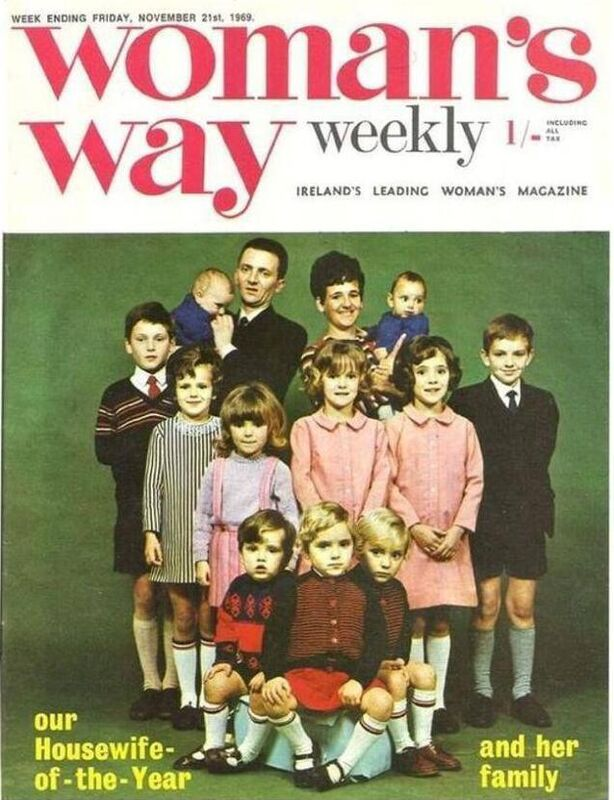

It is, of course, a curated version of domesticity, an aspirational, luxury lifestyle outlined in the protectionist ideals of the 1937 Irish Constitution: ‘The State shall endeavour to ensure that mothers shall not be obliged by economic necessity to engage in labour to the neglect of their duties in the home.’ Yet, as Cassidy’s interviews with the contestants illustrate, this was a promise that the state could not fulfil – and for working-class women, “there was nothing so hard as being a housewife.” One contestant, Ann, had 13 children, including four sets of twins by the age of 31. She describes relying on local food centres to feed her family, bringing her own pots to fill with stew which could be smelt by the other passengers on the bus home.

The reality of the seventies for working families was marked by oil crises, global food shortages and high costs of living. Unemployment rates rose and to combat inflation banks raised interest rates, making it harder to borrow money for homes and cars. Many of the women Cassidy speaks to describe managing ever-expanding families and having to give up their jobs after marriage, making them especially vulnerable to unforeseen factors. Ellen illustrates the precarity of being fully financially reliant on a husband’s income when she was left without “two shillings on the counter” once her husband walked out on her.

The women who entered the Housewife of the Year were a mix of middle and working-class and Cassidy illustrates that their reasons for participating often went beyond a desire to compete for prestige. As Ann points out, the competition provided an opportunity to win a sizeable cash prize along with electrical appliances like cookers and washing machines. It was a shrewd opportunity to improve the challenges of their everyday lives. What is also interesting to me, is that the show also seemed to platform the graft of women outside of their domestic roles. In the clips that Cassidy includes here, women speak openly about what they did when falling on hard times. For example, when her husband became sick, Patricia took on a job delivering post whilst still managing all the housework – and also feeding 450 Turkeys every morning to slaughter in the lead-up to the Christmas period.

Image courtesy of Galway Film Fleadh

The show, whilst reinforcing traditional values, also became increasingly caught up in broader conversations about women’s changing role in Irish society. Gay Byrne, host of the Late Late Show, which is considered to have played a major role in airing discussions about stigmatised issues like contraception and divorce to mainstream audiences in Ireland, also presented the Housewife of the Year competition. We see clips of him asking gently provocative questions to current and former contestants about their views on aspects of the women’s liberation movement. The women Cassidy speaks to reflect on the developing sense of ambition for what they felt they could achieve following their wins, and we see footage of Ann debating a Catholic priest on the topic of birth control on the Late Late Show.

The documentary captures a turning point when the competition began to reflect the shifting attitudes of its contestants in the face of Ireland’s evolving identity and eventually offered an ironic lens into its own obsolescence. Cassidy includes the audio and footage of advocates from Ireland’s Women’s Liberation Movement, articulate, challenging voices who were gathering momentum, alongside moving testimonials of women, now much older, reflecting on the dissonance between today’s world and the one they grew up in. What the film seeks to do is to identify a moment of clarity amongst the broader conservative shift that we are living through. The film was screened a Vue Picadilly as part of the Irish Film Festival in mid-November, in the light of Donald Trump’s re-election and the growing rollback of minority, LGBTQ+ and women’s reproductive rights in the United States.

Agnès Houghton-Boyle is a critic and programmer based in London. Her writing features in Talking Shorts Magazine and Fetch London.